On Sept. 28, a group gathered at the Blue Hills Lecture Hall at UW-Eau Claire — Barron County to attend a “Braille for the Sighted” event hosted by alumnus Alexander Townsend.

According to series organizer Linda Tollefsrud, Townsend has a passion for video games, the clarinet and discussing disability rights as a sight-impaired person.

The event was part of the “Thursdays at the U” series partially funded by the UW-Barron County Foundation. The series involves weekly lectures open each Thursday to the public. The events take place in the Blue Hills Lecture Hall from 12:30 to 1:30 p.m.

Townsend provided an introduction to Braille as a language, the importance of learning it and how to go about reading Braille.

“Braille is a broad thing; it’s a collection of writing systems,” Townsend said. “Each of these systems is referred to as a Braille code.”

Townsend said the codes of Braille primarily differ in their use, cases and the symbols they use to describe things.

Townsend broke down literary codes by base languages from around the world and said while the codes themselves weren’t completely different languages, Braille does vary based on origin.

“In addition to the literary code, there is the Nemeth Code, which is used for math notation, and there is a music notation code for sheet music,” Townsend said.

Townsend went over a few of the reasons for sighted people to learn Braille. He said that blindness is something that could occur in any person.

“The majority of blind people were not born that way,” Townsend said. “Even if you don’t ever need to use Braille, it’s like an insurance policy. If you do lose your sight, you have that to fall back on.”

Townsend said that other benefits of learning Braille include reading without light and opening the mind to language as a whole.

“You’ll gain a new perspective on how language is structured. You can formulate ideas on it and how to go about communicating in general,” Townsend said.

Finally, Townsend said, Braille can help bridge communication gaps between those who are blind and deaf.

“With Braille, you can use the common denominator between blind and deaf people of a sense of touch which can be used to communicate,” Townsend said.

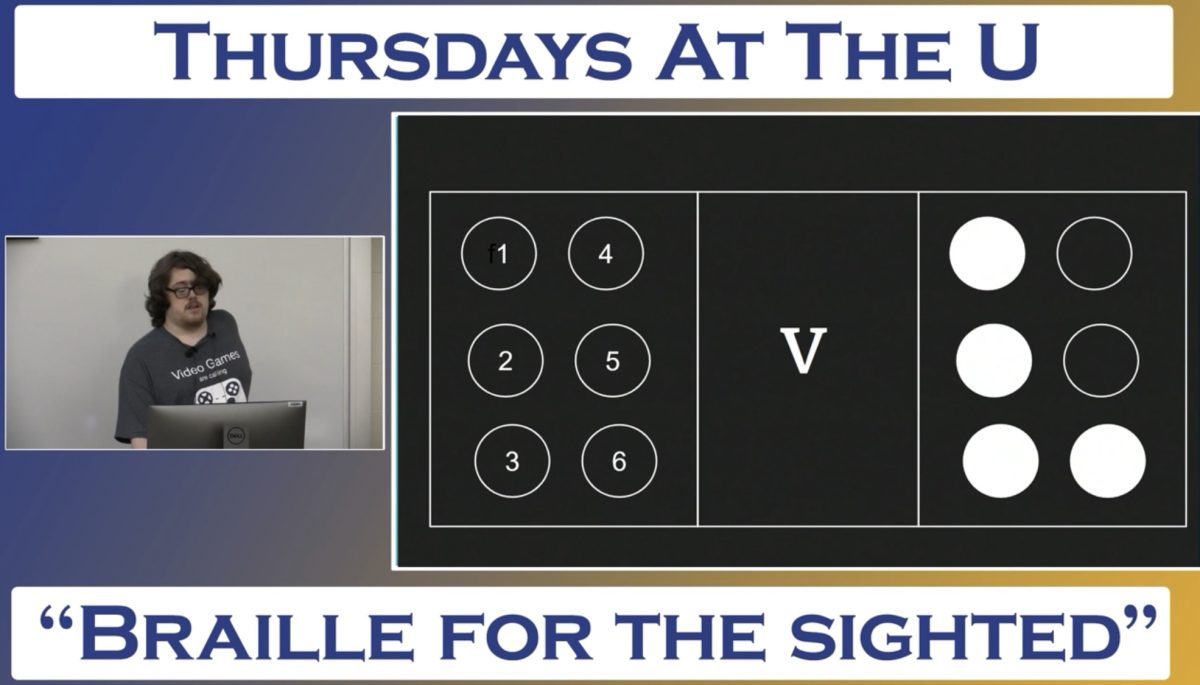

Moving on, Townsend gave an overview of how Braille works and how to read it. The most basic level, as Townsend said, is the Braille cell. The cell is a structure of six dots used as a vessel to hold characters.

Townsend said that each dot in a Braille cell is associated with a number based on its placement. The numbers are used as a way to label and reference which dots are being used. To construct a character, a specific number of dots within the cell must be “filled in.”

In a classroom-style lesson, Townsend went through the letters of the alphabet as well as common symbols and numbers with the group. He used cell diagrams as a visual aid.

“Because there is no texture, these diagrams are not real Braille — they’re knockoffs,” Townsend said. “They’re like ‘I can’t believe it’s not Braille.’”

With engagement from the audience, Townsend spent time explaining how to combine characters to form and read simple sentences.

At the end of the presentation, Townsend responded to questions from attendees about the logistics of reading Braille, its prevalence in society, and how best to learn further.

A recording of the presentation can be accessed at the Rice Lake Community Media website.

Wojahn can be reached at [email protected].