Mitchell v. Wisconsin sparks controversy over Implied Consent

A panel of lawyers and professors discuss the ramifications

More stories from Taylor Hagmann

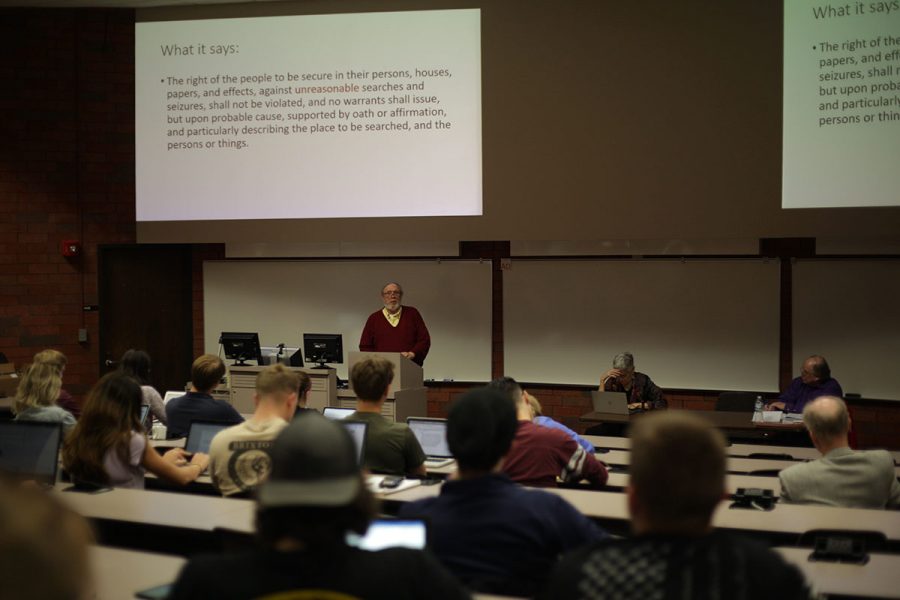

Photo by Gabbie Henn

Professor Michele LeVigne, Professor Michael Fine and Assistant District Attorney Roy La Barton Gay were the featured panelists at Thursday’s event.

In order to receive a driver’s license, people must agree to terms which give consent to have their “breath, blood, or urine” tested for drugs or alcohol, should they be suspected of driving a vehicle while intoxicated.

This section of the Wisconsin state law is called “Implied Consent,” because it says that if someone is operating a vehicle on public roads, then they can either consent to testing for intoxicating substances if there is probable cause, or withdraw consent and lose their license for a year.

This is, more or less, what happened with Gerald Mitchell, of Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Except, he was unconscious when they drew his blood.

In May of 2013, Mitchell was detained by police due to reports of erratic driving. When police caught up with him, he was walking along a beach, wet and covered in sand. The officer detained Mitchell when he verbally admitted to consuming alcohol.

On the way to the police station, Mitchell became “lethargic” and the officer instead brought him to a hospital, where Mitchell became unresponsive. While he was unconscious, the officer had hospital staff draw Mitchell’s blood without a warrant to ascertain his blood alcohol content.

Mitchell claimed drawing his blood while he was unconscious was in violation of his Fourth Amendment right, which, in the U.S. Constitution, says people have “the right … to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

He said he never had the opportunity to withdraw his consent; therefore, they should not have been able to use his blood test as evidence in a trial. He tried to have the resulting evidence suppressed, but his appeal was unsuccessful.

In all of Mitchell’s previous attempts at an appeal, the juries have ruled in favor of the State, claiming Implied Consent. However, Mitchell’s continued appeals have brought the case before the U.S. Supreme Court, and they have decided to review it.

The case has sparked controversy and discussion, one of which took place in Hibbard last Thursday afternoon.

Eric Kasper, a political science professor at UW-Eau Claire, hosted a panel to debate the issue of Implied Consent and its intricacies.

“Part of why we were drawn to the case is … (because) Wisconsin is tied to (it),” Kasper said.

The panelists were chosen to represent all sides of the matter, Kasper said. The featured panelists were Michael Fine, a UW-Eau Claire political science professor, Roy La Barton Gay, assistant district attorney of Chippewa County and Michele LaVigne, a professor of law from UW-Madison with experience as a public defender.

All have slightly different opinions on the case, and all were given time to defend their positions.

Fine went first. He said he believes there was sufficient probable cause, due to Mitchell’s behavior and admittance to drinking; therefore, a warrant was unnecessary. Fine said Mitchell gave consent when he got his license, like everyone else who has one.

La Barton Gay was second. Though he is a prosecutor who likes to have solid blood evidence of intoxication, he said Mitchell wasn’t allowed the opportunity to withdraw consent as he should have been.

But the case isn’t about Mitchell versus the government, La Barton Gay said. The case should be Mitchell versus everyone driving, and their right to life, as determined by the Declaration of Independence. When people like Mitchell drive while intoxicated and cause an accident, “there are no winners.”

La Barton Gay said, because Mitchell’s behavior caused him to lose consciousness, he forfeited his Fourth Amendment right by driving impaired.

LeVigne was the final panelist. LeVigne said the police should have gotten a warrant to draw the blood. She said warrants protect people. They are required unless under exigent circumstances.

However, the courts ruled in 2013 in Missouri v. McNeely that alcohol dissipation in blood was not an exigent circumstance. Since warrants only take 15 minutes to obtain with today’s technology, LeVigne said there was no reason why that officer should not have gotten a warrant.

Corey Sather, a third-year computer science student who attended the panel, said, although he went into the event Thursday night believing the officer should have gotten a warrant, he left believing it was unnecessary.

“The concept of getting a license as a contract with the government is an interesting idea,” Sather said. “I just wish I was more aware of it. I would like to see them explicitly outline the rights when you get a license.”

Kasper said he expected the U.S. Supreme Court to make a ruling sometime in June to determine whether or not the blood draw of an unconscious person without a warrant is constitutional.

He said their decision will likely affect future cases in terms of how consent and warrants should relate to one another.

Hagmann can be reached at [email protected]