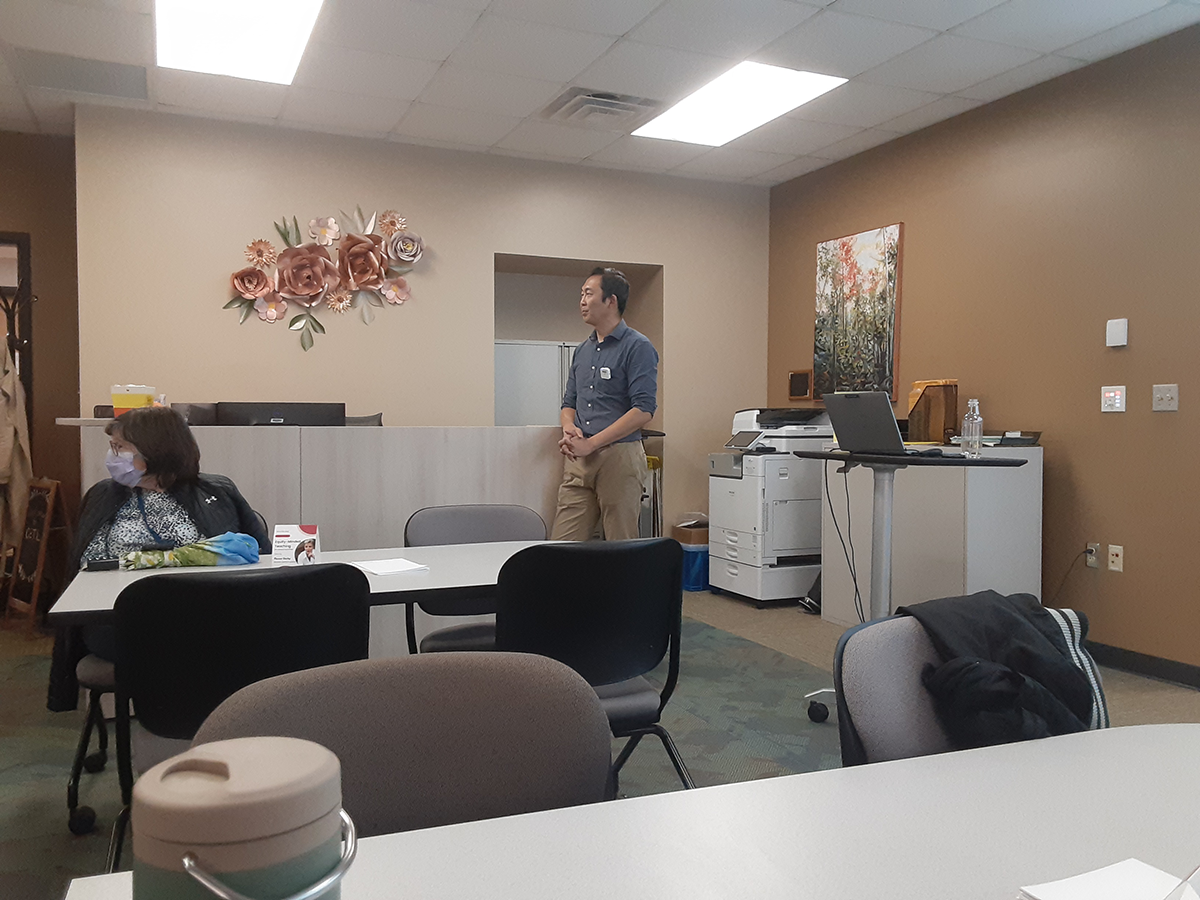

A UW-Eau Claire faculty/staff forum called Conflicts Between Expatriates and Host Country Nationals During the Acculturation Process was led by Dr. Longzhu Dong last Wednesday.

The talk covered the acculturation process, as well as the four different strategies that can be used to assimilate into a new culture.

Dr. Longzhu Dong, associate professor in the College of Business Management and Leadership Programs, defined the groups involved in the acculturation process.

“Expatriates are defined as a group of people who either live or work in a different country for more than a year,” Dong said. “They want to work and study in a different country.”

The other group involved are the host country nationals. They are citizens of the country they live in and are entrenched and familiar with local culture.

Dong led a study on diving into the acculturation process and what factors impact the success of expatriates. He said the purpose of the study was to explain how conflicts emerge between expatriates and host country nationals and how the conflicts can change over time.

Dong said there are two major types of differences between host country nationals and expatriates: surface level and deep level.

Surface level differences are visible or obvious differences, according to Dong, who described a few.

“They look different. Different color skin, different language, different food, different way of dressing themselves,” Dong said.

“Then there is something subtle, deep level – Beliefs, religion, values, work ethics, work styles. They will only be revealed through interaction. You cannot tell what that person is like until you work with them for a couple weeks or months,” Dong said.

Dong identified four acculturation strategies. Integration is where an expatriate tries to integrate their differences with host country nationals. Separation is the opposite, where an expatriate wants to remain as they are rather than changing with the culture.

According to Dong, assimilation is where an expatriate totally becomes a part of the local culture. Marginalization is where an expatriate tries to keep themselves away from the culture, and is rare in most situations.

The study also developed a three-stage model on the progression of acculturation.

“Stage one is when categorization is formed based on surface-level characteristics. Stage two is when the categorization is formed based on deep-level characteristics. Stage three is when conflicts emerge on the deep level due to changes from acculturation,” Dong said.

Dong said that the categorizations come into play when expatriates’ deep-level characteristics agree or disagree with the host country nationals’ expectations.

Dong said an example of this is if an expatriate’s surface level is different from the host country’s, but it is revealed that their deep level is similar. This is where expatriates find the most success, when the host country nationals learn that they are actually similar to each other.

Dong also gave another example: if an expatriate’s surface level characteristics are similar to the host country’s, then it is often assumed their deep levels are similar as well. If they are not, that is when the worst conflicts can emerge.

“If we perceive we’re similar, but then we figure out we’re not the same at all, that feeling of surprise and being betrayed will raise the conflict significantly,” Dong said.

Dong expects that the study will help us understand how conflicts emerge and how they can change over time. He hopes it will help expatriates succeed while being abroad.

“Conflict is dynamic in nature, and the same is for social categorization,” Dong said. “It depends on you and what accuration strategy you choose.”

Sherry can be reached at [email protected].