The value of a vote

Why the electoral college dilutes citizens’ voting clout

More stories from Stephanie Kuski

Photo by Submitted

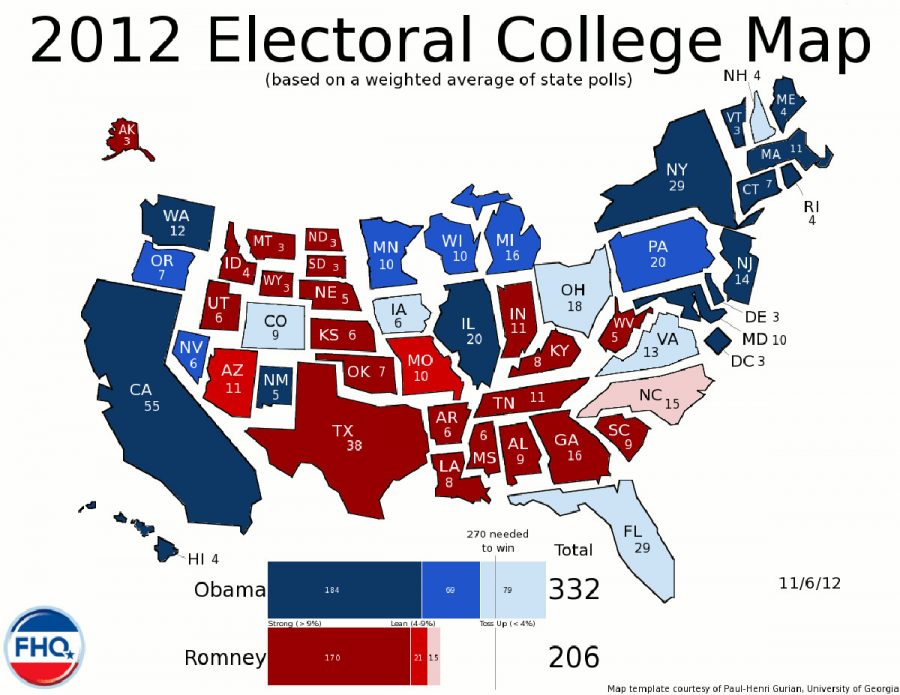

A map of the electoral votes allotted to each state and the 2012 tally of electoral votes shows how some votes are more significant based on the state you live in.

This election marks the time many young Americans will encounter their first opportunity to vote, myself included. The voting process is still, in some ways, foreign to me, although I try to educate myself on the ins and outs as often as I can.

But the more I learn about our election system, the more I realize my vote doesn’t count as much as I was led to believe.

I recently stumbled upon an opinion piece from a young Huffington Post writer outlining how the electoral college dilutes the voting power of the people, effectively giving some citizens more voting power than others.

Let me start by putting it this way: Citizens of the United States do not directly vote for president. Once their vote is cast, the political party whose candidate received the majority in a particular state choose electors who cast the real votes for president.

Although this process may have some benefits (it’s worked pretty well the past couple centuries), it’s undemocratic to lead people to believe they directly vote for president when that’s not the case.

There are a total of 538 electors who comprise the electoral college and it takes 270 electoral votes for a candidate to be elected into office. States are allotted electoral votes based on population and their representation in Congress. But each state is given a minimum number of three electoral votes regardless of population to ensure that smaller states maintain some voting power.

Except for Maine and Nebraska, all states have a “winner-take-all” system, in which the party that wins the majority vote in a particular state appoints the electors for that state. Although electors are typically loyal supporters of their political party, they do not have to cast their ballot in the direction of their state’s popular vote. This habit is called “faithless electors.”

This indirect election system is undemocratic not only because so many citizens don’t understand how the voting system actually works, but also because a candidate can win the White House without receiving the most popular votes. There are many other underlying problems associated with this electoral system that need to be brought to light.

Unequal distribution of electoral votes

If the amount of electoral college votes were directly proportionate to a state’s population, smaller states would lose out on a lot of voting power. To counteract this, every state gets a minimum of three electoral votes regardless of population.

But this process renders some votes less significant than others based on the state you live in.

Fairvote.org explains this dilemma by comparing the voting power of Wymoing to Texas. Since Wyoming automatically gets three electoral votes for their scare population of 532,668 citizens and bigger states like Texas get 32 electoral votes for their population of almost 25 million, each individual vote in Wyoming counts almost four times as much as an individual vote in Texas. That’s because Wyoming has one elector for every 177,556 people and Texas has one elector for every 715,499 people.

When smaller states get more electoral votes per person than larger states, the value of your vote essentially depends on the state you live in.

Swing states

States that generally vote for the same political party are called safe states and states that historically maintain equal support for both parties are swing states, which are are crucial for deciding the outcome of elections.

Under the electoral college voting process, a vote is only as valuable as its ability to influence the majority vote of a state because the citizen’s majority vote determines which candidate will receive all of the electoral votes from their state.

If you live in a safe state and you vote against your state’s normal party lines, then your vote is essentially worthless. If you live in a swing state, your vote is marginally more significant than the vote of someone who lives in a safe state.

Contested elections

Four presidents have been elected who did not win the popular vote, according to a BBC article.

Most recently in 2000, Al Gore won 48.4 percent of votes compared to 47.9 percent of votes for George W. Bush. But because Bush won 271 electoral votes compared to 266 for Gore, Bush won the presidency despite losing the popular vote.

Imagine this year’s election is decided by electoral votes rather than what citizens voted for. Not only would we have a similar uproar as in 2000, but mistrust will easily build in light of government entities taking over the democratic process.

A note from the other side

Despite the problems within the electoral college system, it’s still respected for its historical roots and usually reflects the popular vote.

The electoral college gives weight to smaller states and requires a candidate to get a spread of votes from across the country, living up to the checks and balances of the Constitution. Without the electoral college, presidential candidates might be chosen by large metropolitan areas and squander rural voters in comparison.

This system also enhances the status of minority groups because minority voters are concentrated in states with the most electoral votes. A direct election would therefore damage the interests of minority groups because their votes would be overwhelmed by the national popular majority.

Despite the clear faults in our election system, it is just as important (and perhaps more important this year) to vote. There isn’t going to be any easy fix to this centuries-old system, but that doesn’t negate the fact that we as a collective community need to exercise our duty to vote as well as educate ourselves on the face value of our election process.