“Capitalist Realism” by Mark Fisher was one of the first books I read this year, and I finished it almost the day I bought it. It is a short but powerful critique of capitalism in the form we see it today.

Fisher comes from a new wave of philosophers who have become famous from their internet presence, such as Slavoj Zizek or Nick Land. Fisher actually started as a blog writer and most of his books are based on his blog K-punk.

Writing on the internet had given Fisher freedom to pursue topics of interest outside of academia or big-time publishing. It’s in his blogs that Fisher formulated many of the ideas present in “Capitalist Realism.”

The book itself was published by Zer0 books, a small publishing company that blew up because of Fisher’s work. The sudden popularity surge of the book in the 2010s showed its relevance to thousands of readers.

As an experience, the book is both thrilling and terrifying. It’s both of these things because it describes our current landscape so well.

The main thesis of the book is that it’s impossible to imagine another alternative to capitalism. We are left stuck in a dissociative age where change is constant, but it also feels like nothing ever changes.

One of the ideas that stuck out to me was the description of hauntology. A term coined by Jaques Derrida, hauntology describes the persistence of forms of the past within the present.

Hauntology is something I see constantly, especially in the visual arts. The contemporary art world is full of rehashes of art styles from across history, but there’s no idea of what the future is supposed to look like.

Artists like Banksy constantly reference art history in a cheap effort to make a statement about art without really saying anything new.

There is a resurgence in collage as an art and form of writing, as the current cultural landscape feels more like a collection of images and ideas from around the world and history rather than any coherent narrative.

Fisher says hauntology is present in the 2006 film “Children of Men”, where Greek statues and masterpieces from art history look down upon a wasted landscape with a dwindling population.

The cultural icons of the past have become sterile, but they’re also all we have left to hold on to. Our society has no center, no germinating power, so we look for it in the past.

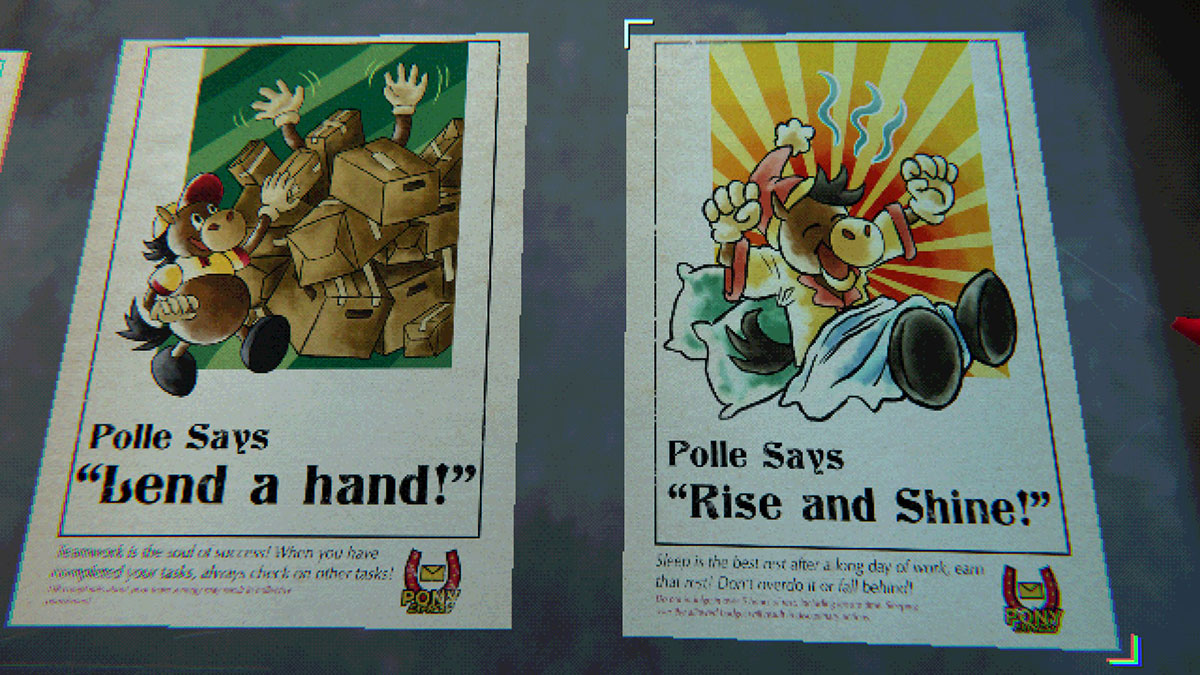

The centerless society is also visible in business systems. More and more institutions present endless webs of bureaucracy where there is ever more surveillance and rules but no one human person controlling it all.

Franz Kafka predicted these systems with remarkable accuracy in books like “The Trial” and was famous for describing the feeling of alienation they produce.

There’s also the matter of symbols becoming more important than reality. I think of how workers are expected to perform fake enjoyment of their jobs or how Gucci bags are worth more because of the brand than the actual material.

All of this sounds depressing, and it is. Luckily, Fisher also coined a new term for the modern type of depression, which I find to be incredibly accurate.

Fisher’s term is called “depressive hedonia,” which is “ … not … an inability to get pleasure so much as it is … an inability to do anything else except pursue pleasure.”

Going on the hamster wheel from one pleasure to the next, there’s always an emptiness that persists.

Fisher observed it commonly among his college students, and I’d be hard-pressed to say I don’t experience the same thing.

He sketches outlines for societal change in the last chapter, but I don’t think any of them sound particularly effective. It’s much too vague.

However, the fact that the book so accurately describes the current situation is something that can inspire optimism.

The proliferation of intelligent publishing houses, blogs and internet philosophers outside academia shows there’s still a place for serious critical thinkers who have ideas that feel genuinely new and fresh.

I’d recommend “Capitalist Realism” as a required reading for any serious student of philosophy or modern politics.

Sonnek can be reached at sonnekrl6881@uwec.edu.