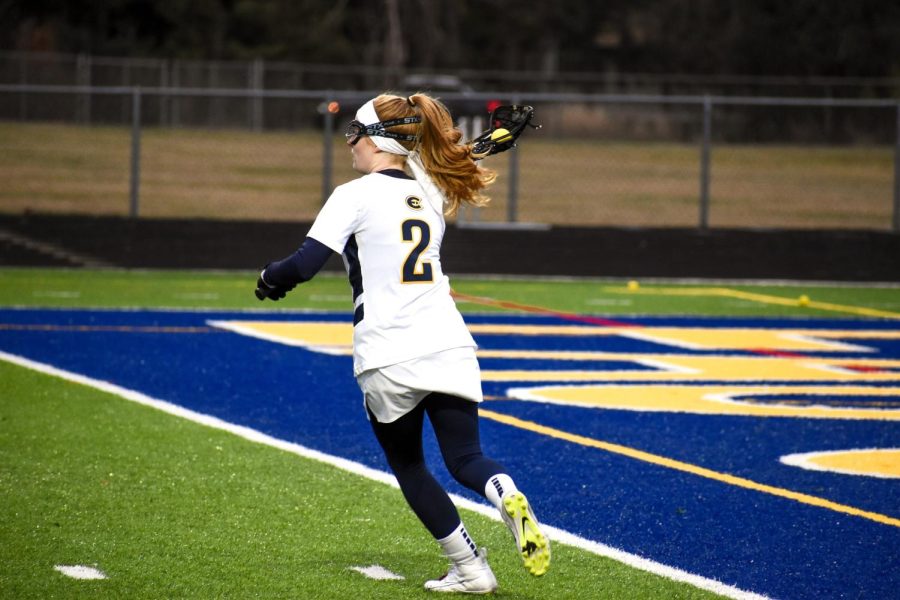

Nicole Robinson

Nicole RobinsonIn 1972, an education amendment to the Civil Rights Act known as Title IX paved the way for gender equality at all levels of interscholastic athletics.

As the amendment states, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

| “We like to keep masculinity and femininity as separate as we can.” –Pam Forman Title IX expert |

The amendment requires educational institutions to maintain policies, practices and programs that do not discriminate against anyone based on sex in all arenas of public schooling, according to the Department of Education.

Because of Title IX, many men’s sports have been cut in an effort to comply with the amendment. For example, UW-Eau Claire has many men’s club teams that are recognized athletic programs at other universities. Some lobbyists, like Phyllis Schafly, are trying to turn Title IX into an opportunity provider for the under-represented sex, instead of an opportunity-impeder for the most-represented sex.

While the amendment has given women athletes the opportunity to compete at all levels and in all sports, it remains a very rare occurrence for women to try out for what have been societally labeled “men’s sports,” Interim Director of Athletics Tim Petermann said.

And while women compete in “men’s sports” at a young age, like baseball and wrestling, there is a bigger barrier at play as to why women don’t continue playing “men’s sports,” associate professor and Title IX expert Pam Forman said.

Something rare in the air

Title IX has paved the way since 1972 for women in athletics in many ways. The U.S. Department of Education states that women participating in college athletics has increased fourfold; the number of women in high school sports have increased eightfold, and U.S. women won a record 19 gold medals in the 1996 olympics.

However, strides must still be made as women are not participating in male-dominated sports, Forman said.

“The basic structure of colleges everywhere is that girls don’t play male-oriented sports,” sophomore swimmer Emily Diehl said. “They wouldn’t want to damage the social structure by allowing females and males to combine in a sport.”

Women’s hockey, at both the high school and collegiate level, is a relatively recent addition to athletics. This winter alone, between four and five high schools added a women’s hockey program, Forman said.

“Now women’s hockey is on the map, so to speak, and it’s not as big of a novelty anymore,” women’s hockey coach Mike Collins said.

In the past, and even still in the present, women with an interest in hockey would have to play against men. Collins said every so often, there are women going through the program who played at the male level in high school.

“It would be to their advantage to play on a competitive men’s team and we gotta give them credit for sticking it out in a sport dominated by men and overcoming barriers,” he said.

Senior rugby player Marcy Reynolds said the barriers women have to often deal with in a masculine sport are socialization and systematic pressures.

“There’s a socialized, reinforced idea that women are fragile,” she said.

“With something like football, men come out to watch it as a joke. Labeling a sex on a sport is deeply imbedded in our society.”

Instead of asking why this is so rare, Forman said perhaps a different question should be posed: How can we celebrate the accomplishments of women in sports in such a short amount of time?

“It’s more of an intimidating step for women,” senior golfer Maggie Loney said. When Annika Sorenstam and Michelle Wie crossed over the gender border in professional golf recently, Loney said she didn’t know why it was such a big deal.

“I thought it was great to see a woman out there competing with the guys,” she said. “I think more women should do it.”

In 1997, Eau Claire women started rugby, giving them their own opportunity for gender equality, junior rugby player Allana Wood said.

“We (play rugby) to empower all of the women who haven’t had the opportunity to play a physical sport,” she said. “This is something that was unavailable for us to play 20 years ago.”

Those girls are fragile

At a very young age, Forman said our society reaffirms certain societal norms. For instance, a boy is awarded if he beats up somebody who teased him, but if a girl does that she is told not to fight back, Forman said.

“Girls are not rewarded for being tough in this society,” she said.

Is the reason women don’t go out to compete in traditionally men’s sports because they aren’t physically tough enough? Biology confirms that, yes, there are in fact differences in body type that make certain sports harder for women to play than men. The center of gravity of women for tackling in football and differences in muscle mass are examples.

However, Forman said it is a fact that 95 percent of both men and women cannot play football. On that basis, Reynolds said, “You can have a 5-foot-11-inch female who lifts weights and a 5-foot-three-inch male who is unathletic and the girl would beat him.” Athleticism is still relative to a case-by-case basis, she said.

Diehl said growing up with three brothers gave her something extra that didn’t have anything to do with biology: drive. She said if she was facing her sister in a swim race, she would want to beat her, but if she was facing her brother she would try much harder to beat him.

“If I had a passion to play football or if people were saying ‘You can’t play, you’re not big enough or strong enough,’ that would push me to go in and prove them wrong,” Diehl said.

Similarly, wrestling coach Don Parker said the two women who wrestled on his team in his 29 years of coaching had a drive to compete. In wrestling tournaments across the nation that included other women wrestlers, the women would take it upon themselves to travel and compete with those other women.

“There is a stigma that men are stronger and faster, but in some cases women are stronger and faster if they are physically determined,” Wood said.

Forman agreed, citing distance running and endurance swimming as sports where women exceed men in some instances.

“To say that women don’t have the strength, flexibility, and ingenuity to (wrestle) is absurd,” she said. “I would argue that gymnastics, and sports like that, are very much based on strength.”

But the strength and muscularity gymnasts and swimmers develop often are hidden, Forman said.

“We don’t want women to excel (in masculine sports),” she said. “We prefer women to go out for sports that reaffirm their femininity.”

Loney said golf is one of the few sports where women can compete against men without physicality coming into play. While men usually can hit the ball farther, the difference in tees evens it out, she said.

“I’d never be afraid to take a guy on in the game of golf,” she said. In fact, Loney said, she sometimes plays golfers from the men’s team as motivation.

What Wood often hears women say in response to a sport like rugby is, “I’m not strong enough, I can’t do it,” she said.

“It’s not a matter of being aggressive enough, it’s a matter of having confidence in being able to do it.”

Flipping the gender card

While rare, men who compete in women’s sports bring to the surface very similar issues to those of women in men’s sports.

“If a male decides to become a figure skater, we immediately discuss his sexuality,” Forman said. “It’s absurd, there’s no reason to do that except that we like to keep masculinity and femininity as separate as we can.”

The most common female-dominated sport men go out for is field hockey, Forman said. At the high school level, the media coverage field hockey receives immediately is related to sexuality because of the skirts the women wear, Forman added. Therefore, if a man goes out for field hockey and wears a skirt, his masculinity is attacked.

There have been cases of synchronized swimming as well, Forman said. And again, it’s a sport that people call sexuality into question for.

“Try the next time when you’re swimming just to bring your leg out of the water . there’s nothing harder in the entire world,” Forman said.

Wood demands that we, as a society, ask ourselves various questions.

“Why can’t women play rugby? Why can’t a man play women’s softball if he wants to? It’s just, as with any other setting, that there are always going to be people judging,” she said.

Just as the women on the Eau Claire rugby team have been harassed about their sexuality, Reynolds said some men have to endure the same. When men are on the dance team or in cheerleading, they are surrounded by what our society deems to be “ideal women.” Yet, the men in these activities often are labeled gay, Reynolds said.

“We’re so trapped in these gender mores that really constrain the possibilities for both sexes,” Forman said.

Harassing circumstances

Even though Katie Hnida was the first woman to score points in a Div. I college football game, she also became one-of-six women at Colorado University to be harassed by members of the football team, according to the National Organization for Women.

Because of this case, and several others, some of the women athletes of Eau Claire would be very hesitant to attempt a male-dominated sport.

As freshman defender Allison Smith of the women’s soccer team said on the subject, “I’d be very uncomfortable and nervous. Teammates, coaches and other girls would make me feel very uncomfortable, and harassment is a big part of it.”

Also, the idea that you may get along with your team, but not those you’re competing against is scary, Wood said.

U.S. Department of Education Secretary Richard W. Riley said in a journal article that Title IX has made extensive progress in the past 25 years; however, we still can make lengths toward harassment cases and operating expenditures.

Reflecting on women in the military, Forman said a previously all-male institution with women assimilated into it is not a pretty picture.

“For a woman to have the guts to go out for a men’s sport, to try to be taken seriously and put up with the harassment she would endure is truly exceptional,” she said.

On the other hand, Parker said, outside of the men being a little uncomfortable at first, there weren’t any harassment issues.

Likewise, Loney said her matches against members of the men’s golf team have been comfortable.

However Wood and Reynolds have had their run-ins with harassment on the rugby team.

“It hurts me when people assume rugby players are big lesbians … do they say it because it’s male-centered because of being physical, or are they intimidated?” Wood said.

Similarly, Reynolds has encountered Harassing comments as a rugby player.

“Sexuality is called into question because people feel the need to categorize and label something that is different,” she said.

Moreover, when women athletes drive themselves past these instances of harassment it truly shows their strength, Forman said.

“It takes a particularly gutsy woman who can defend her femininity and her prowess . a really strong woman

who can go out for a men’s sport,” Forman said.

Light at the end of the tunnel

While progress still can be made in integrating women into athletics, many believe there will be a day when gender and athletics won’t be an issue.

Women in pole vaulting only have been around since 2000, and the women’s marathon came in around 1984. Forman said a delay of this sort is blasphemous.

“Men have been doing these for so long . and 100 years from now, we can really compare more when women have had more opportunities,” she said.

Diehl said she easily can foresee a day when women run as fast as men in track or compete in basketball and football. However, she said, it won’t likely be in our lifetime.

“If women were allowed to grow as men do from an early age, they could compete,” Reynolds said, adding the social structure isn’t likely to change for at least another 100 years.