At a time when political correctness has become an instilled fear rather than polite gesture or habit, a film called “Rory O’Shea Was Here” comes out of Ireland and redefines what it previously meant to be crippled, handicapped or, as is currently preferred, disabled.

“Rory” was released in 2004, the same year that the MTV documentary about full-contact wheelchair rugby, “Murderball,” came out. Together, they paint an entirely different picture of disabilities for mainstream audiences.

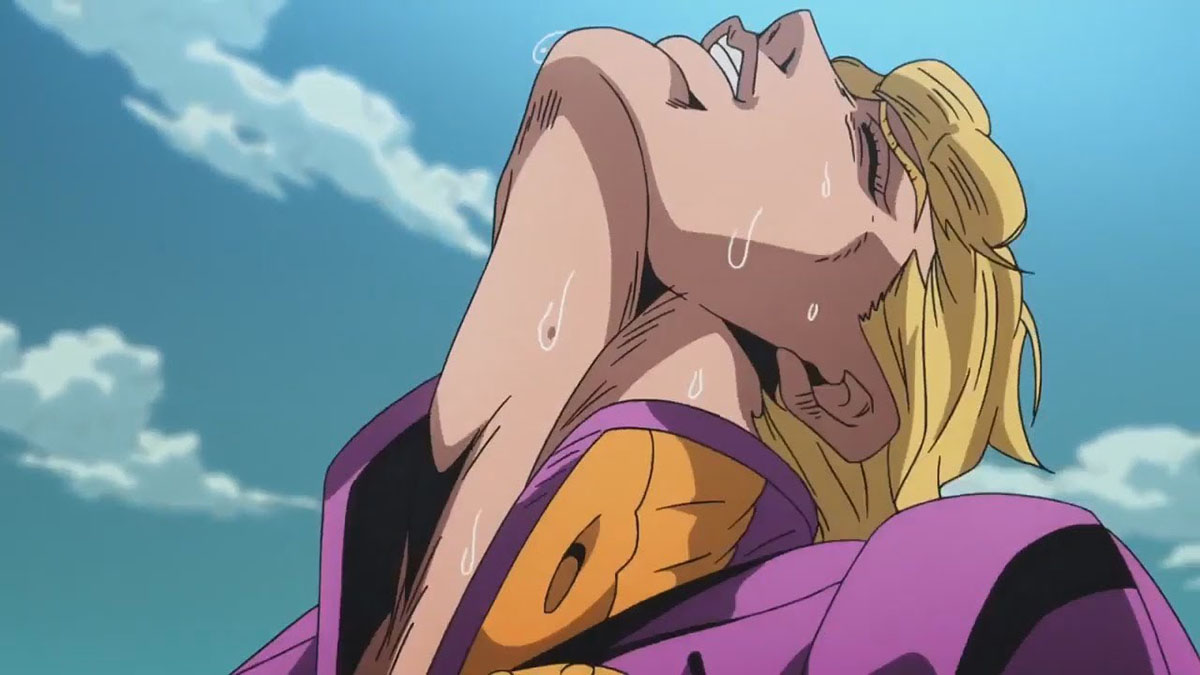

“Rory” opens at Carrigmore Residential Home for the Disabled, where a free-spirited young man with muscular dystrophy ushers in a whole new outlook on life. Rory, who wears unruly spikes atop his blonde dome, immediately disrupts the management, schedules and several of the residents at Carrigmore.

One day, Rory bumps into Michael, a young man with cerebral palsy and nearly unintelligible speech. With charismatic ease, Rory defies the rest of the staff by understanding Michael’s speech. Michael coins it a “gift” and follows Rory from there on.

This includes an unapproved night on the town in which Rory asks Michael, “Don’t you want to get drunk, get arrested, get laid?”

The duo takes donation money from Carrigmore and heads downtown. When a pair of girls asks Rory if it’s OK to take the donation money, Rory promptly says, “It’s funding for the needs of the disabled. I’m disabled and I need a drink.”

When they come home, drunk and smiling, let’s just say the management isn’t too happy.

Representing another in a long line of futile attempts to live on his own, Rory treks out of Carrigmore later that week with Michael to meet with a board of representatives that oversee and approve independent living for the disabled. The board makes it perfectly clear that, despite all arguments, Rory is too irresponsible and too rebellious to successfully live on his own.

Michael has lived in institutions since his mother died and his father walked out on him – so basically, all of his life. Rory’s perspective of institutions such as Carrigmore, which act as prison-like environments that constantly remind him of how dependent he is on others, forces Michael to do something drastic.

Michael and Rory return to the board, but this time asking for Michael’s independence. With no hesitation, the board agrees but has to fulfill one of Michael’s conditions – a full-time live-in interpreter named Rory O’Shea.

“Rory O’Shea Was Here” is not another film in a long line that asks viewers to empathize or feel sorry for its protagonists (i.e. “Rain Man,” “I Am Sam,” “What’s Eating Gilbert Grape?”). “Rory” actively shows viewers the story of two young men not unlike yourselves (at least, not in most respects). Rory and Michael are real characters who love, mourn, hate, neglect and hurt like everyone else.

The aspects that hurt the film the most are its predictable conclusions, off-beat humor and overdone dramatic ending. Sadly, Rory and Michael can’t have the complete package of a success story, as everyday situations once again remind them that they aren’t like everyone else. Why can’t they find love with an “able-bodied” woman? Why can’t they dance? Why do people stare and then look away when they turn toward them?

“Rory” starts as a punk film with a unique twist and message, but drastically sways back towards the sappiness of Hollywood after-school specials and clich one-liners of network sitcoms.

That’s not to say there isn’t something to take away from “Rory.” The best scenes include Michael and Rory’s caregiver Siobhan (passionately played by Romola Garai), a beautiful blonde who teaches Michael more about life and love than he cares for.

Steven Robertson plays Michael with melodramatic accuracy, while James McAvoy plays the always-up-for-a-fight, cocky, punk Rory.

Whether or not its formula works as a film is irrelevant; “Rory” (with help from films such as “Murderball”) boldly initiates a filmic world that takes disabled characters to where they belong – with everyone else.