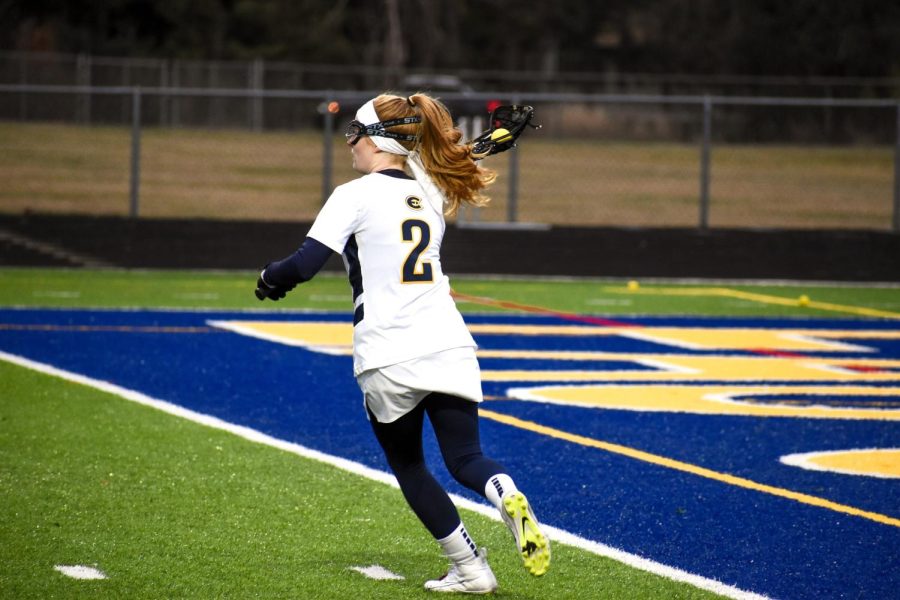

Janie Boschma

Janie BoschmaJunior Nicole Lillis’ disdain for the U.S. Army and the government that controls it all comes down to a preventative measure that many in the United States and throughout the world take for granted nowadays.

It all comes down to a technological advancement that helps children ward off the flu and chicken pox.

It all comes down to a series of elixirs intended to protect soldiers in the event of a biological weapon – vaccines.

“I’m not going to tell you the fluffy story of the military,” she often tells people when they ask her about her time in the service.

Lillis suffers from painful symptoms that are typically associated with autoimmune disorders. Lillis said she and doctors believe the vaccines the Army gave her to take at the beginning of her military career caused her immune system to become hyperactive.

Leading researchers agree and have shown a link between military vaccines and autoimmune disorders, claims and connections that the U.S. government emphatically denies.

Basic training

Lillis, 29, began her college education at UW-Eau Claire in 1998 as a criminal justice major. In January 2001, she decided to join the military, something she said she knew she wanted do since she was 16.

“I really wanted to see the world and travel,” she said. “Everyone has their own reasons for joining. Some do it for money; some really want to do it. I just wanted to do it.”

In high school, Lillis wanted to join the Air Force, but instead chose the Army, initially enlisting in the Airborne program, where she could “jump out of a perfectly good airplane.”

She began her military service by reporting to Fort Leonard Wood, Mo., for basic training.

She said she remembers getting onto trucks and traveling to the Military Entrance Processing Station, which prepared her and the rest of the incoming recruits for the weeks ahead. There, soldiers got haircuts, purchased toiletries and got medical examinations, which included receiving the vaccines. Lillis said she and the other soldiers received 12 vaccines that day, one of which was experimental.

She said the soldiers then got back on to the trucks and went to their basic training units where the “drill sergeants were lined up waiting.”

The sergeants screamed at the soldiers the moment the soldiers stepped off the trucks, she said, immediately making the recruits “get down and push.”

Two months into the program, the symptoms began, she said. She began having extreme pain in her pelvis and joints, but kept telling herself that it was just the training catching up with her and that she wasn’t going to be one of those who didn’t finish.

After eight weeks of the physical gauntlet and excruciating pain, Lillis graduated from basic training. Immediately after she began training to be a military police officer.

“When you’re going through it you’re like, ‘this is hell,'” she said. “But basic training was a riot. When you’re done, you look back and say to yourself, ‘I did that.'”

Once the programs were complete, she said the drill sergeants acknowledged the soldiers’ hard work and gave them all advice.

Despite the stress fracture in her pelvis keeping her from heading to Fort Benning, Ga., for airborne training, one drill sergeant told her not to not pursue the training for other reasons.

“My drill sergeant looked me in the eye and said, ‘The Army will never be worth your health,'” she said. “I will never forget that.”

Pain continues

The completion of basic training and military police training was bittersweet for Lillis whose complications got worse shortly after finishing the programs.

She went to a civilian physician who was unable to find anything wrong with her body.

“I remember being so tired and in so much pain, but I just figured that it all had to do with the physical demand of basic training,” she said. “So, I just pushed through it.”

Lillis reported to Fort Hood, Texas, in June 2001 for her duty assignment where she worked for some time as a patrol officer and then moved to being a 911 dispatcher. There, she said her unit gave her a lot of flak for not being able to run like them due to the extreme pain she was in.

One night while at Fort Hood, Lillis said she woke up to go to the restroom when she collapsed onto the floor and vomited continually. A doctor at the military hospital examined her and diagnosed her with bursitis, joint inflammation and gave her high doses of ibuprofen for the pain.

Dead ends

Lillis said her pain worsened through her time at Fort Hood, and she continued receiving the same diagnosis each time doctors examined her at the military hospital and received the same treatment of ibuprofen and cortisone injections. One doctor went as far to give her Zoloft, an anti-depressant, even after Lillis repeatedly told the doctor she was not depressed.

Finally, a breakthrough came in January 2002 when the doctor diagnosed Lillis, 23, with fibromyalgia, a disease that causes severe muscle, joint and bone pain.

The diagnosis led to the military honorably discharging her in May 2003. She remained in Texas until January 2006, when she moved back to Wisconsin and began her own research into vaccines causing autoimmune disorders, which took her into diseases such as Gulf War Syndrome and lupus. This included research that Dr. Pamela Asa conducted, who discovered the connection between the anthrax vaccine and autoimmune disorders.

Lillis said insurance companies view soldiers as having a pre-existing condition, making them ineligible for affordable insurance after their time in the service. So the only affordable health care is through Veterans Affairs hospitals. Lillis initially went to the VA hospital in Tomah for treatment but said doctors attempted to treat “the symptoms and not the problem.”

When she would ask doctors about the possibility of vaccines causing her ailments and noting the experimental one she received, the doctors would ignore the comment or deny it. She said one doctor even went as far as asking if she had an appointment with the psychiatric ward that day after she brought up the vaccine question.

Her luck changed when a Tomah VA doctor referred her to a doctor at the Madison VA hospital who, in the summer of 2006 told her she was on the borderline for lupus and that there was no doubt the vaccines “kicked her immune system into overdrive.”

The vaccines

When Lillis and the other recruits rolled up their sleeves for vaccinations during basic training, they got stuck with 12 needles. Soldiers had to sign an informed consent document before receiving one of the vaccines. She said when soldiers asked why they needed to sign the form, the doctors and drill sergeants told them it was for a pneumonia vaccine.

“We were given the one page to sign without any information on it,” she said, showing the piece of paper she signed that day. “The drill instructors screamed at us to sign the consent document and told us if we didn’t, they would be sure our lives were a living hell. They intimidated us into signing it.”

Under U.S. Code Title 10, Section 1107, when the Secretary of Defense requires or requests soldiers to take an experimental or non-Food and Drug Administration approved vaccine, the Department of Defense must inform the soldiers in writing of the purpose of the drug, the fact that it is investigative or unapproved and its potential side effects before they give it to them. The soldiers must also provide informed consent before receiving the vaccine.

Lillis later found three more pages to her consent form after reviewing her medical records after her time in the service. She said she never saw the pages before getting the vaccine.

The vaccine Lillis received was an investigative pneumonia vaccine that the Department of Defense said the elderly have used successfully for years, saying soldiers should not worry about taking it, according to the consent form. Lillis said she is skeptical if that was really what the vaccine was.

“If the elderly have been taking it for years and it has been effective, then why did we have to sign a consent document?” Lillis asked.

If Lillis or the other soldiers refused to sign the form and take the vaccine, they could have faced a court-martial or a dishonorable discharge for refusing a direct order, according to the Army handbook.

Connections are made

In 1994, Asa, an immunologist, said the path to discovering the connection between vaccines and autoimmune disorders started when Gulf War veterans came to her with rashes, severe pain, headaches and memory lapses.

“It sounded like these people had lupus,” Asa said. “This was uncommon because most of them were men,” noting lupus typically affects women.

Soldiers who served in the United States during the war were experiencing the same symptoms as those serving abroad, so Asa looked to determine what both groups had in common. She said she thought the answer lay in vaccines.

“I said to myself, ‘Oh my God, somebody spiked the punch with an adjuvant,” she said, explaining that adjuvants are added to vaccines to increase their effectiveness.

The daunting task of determining what the adjuvant was and what vaccine it was in began.

Asa had help from a former colleague at Tulane University in Louisiana, Dr. Bob Garry, a leading researcher in creating an AIDS vaccine, who developed a test that showed the presence of squalene, an oil-based adjuvant, in blood in 1997. The test detected anti-squalene antibodies.

She said she sent Garry blood samples from soldiers that came to her with symptoms to have him test for the anti-squalene antibodies.

“When my samples popped hot with anti-squalene antibodies, I just cried,” she said. “My theory was right.”

She said initially the anthrax vaccine wasn’t on the table until the mandatory Anthrax Vaccine Immunization Program started in 1998. Asa said that was when soldiers began coming to her with symptoms again.

They too tested positive for anti-squalene antibodies, she said.

The AVIP ran through June of 2001 when the Department of Defense temporarily stopped using the vaccine due to non-FDA-approved production methods, according to program records.

The program used Anthrax Vaccine Absorbed, which the FDA approved in the 1970s to protect against skin contact with anthrax spores, not inhalation as the military was using it during AVIP, according to the vaccine’s history explained in a U.S. District Court opinion. The FDA eventually labeled the vaccine as an investigative experimental vaccine in the use against inhalation of anthrax spores, according to the opinion, which would place it under Title 10 Section 1107 of the U.S. Code.

Asa tracked the lot numbers of the vaccine, determining that six anthrax vaccine lots had some levels of squalene in them. Later, an independent FDA test confirmed these lot numbers.

“I can’t put into words the look of horror on (the soldiers’) faces and how difficult it was to tell them that the country and the government they were willing to die for had done this to them,” Asa said. “It makes me sick to tell these kids they are positive for anti-squalene antibodies. I hope like hell they’re negative.”

Lillis said she isn’t sure if she received the AVA during basic training because her immunization records were not with her medical records, however, AVIP was still in progress in January 2001.

Court steps in

Several soldiers took their cases to Congress and ultimately brought a lawsuit against the Department of Defense in the form of Doe v. Rumsfeld. As a result, the U.S. District Court issued a temporary injunction on AVIP on Dec. 22, 2003, according to AVIP policy records, which later became permanent in October of 2004, according to the court order.

In February 2007, the Department of Defense reinstituted mandatory anthrax vaccinations for soldiers. AVIP has inoculated nearly 1.8 million soldiers and defense workers since 1998, according to AVIP records.

Government reaction

Both Asa and Lillis said they, along with other soldiers affected by unknown sickness, have been trying to get the government to acknowledge the harm caused by vaccines, but both said they have gotten nowhere.

“I’ve been fighting this since 1994,” Asa said. “I have been receiving hell for it the entire time.”

She said certain officials in the government have accused her and Garry of having an anti-military agenda.

“We don’t have an anti-military agenda,” she said. “I got into this because I am indebted to military personnel who will take a bullet for one of my kids.”

The government’s reaction to Lillis has been the same to most soldiers experiencing problems, Asa said, noting the military would blame the symptoms on things other than the vaccines or would call the soldiers “crazy” and argued that they suffered from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

“Crazy doesn’t cause rashes. Crazy doesn’t cause arthritis. Crazy doesn’t cause these symptoms,” Asa said.

A representative from the Military Vaccine Agency, the Department of Defense body that oversees military vaccine policies, refused to give his name due to Department protocol. He said that protecting soldier health is the No. 1 priority of the agency and the Department and said that all vaccines administered are “safe and effective.”

“Absolutely all of the vaccines are FDA approved,” he said. “There have never been experimental vaccines given to any service members. All service members are given licensed, proven safe and effective vaccines that are approved by the FDA and are administered under the guidance of the American Council of Immune Practices.”

Susan Walker, the Midwest regional analyst for the agency, as well as clinical and communication specialists within the agency, did not comment on questions asked of them.

Pressing forward

Lillis, now an organizational communications major, said her symptoms are ongoing six years later. She recalled an incident that happened during this summer in which she had a severe migraine and began vomiting continually – an event she has experienced in the past. She said the distance to the nearest VA hospital in Tomah, apart from the Chippewa Falls hospital which she said doesn’t accept walk-in appointments, makes it very scary when she does get severely sick.

She said that the muscle, joint and bone pains have gotten worse, noting that at times her back and neck muscles spasm, causing migraines. She also said she started taking the prescribed muscle relaxants again, adding it is sometimes difficult for her to get out of bed in the morning.

Despite her complications Lillis said she doesn’t let it get her down and said she has a support network of family and friends who help her through the struggles. She said she doesn’t want people to feel sorry for her because she doesn’t feel sorry for herself.

“It is just something that I live with,” she said.

She said she doesn’t regret the experiences of the Army. Although she said she would rather have her health, the events of the last six years have shaped her into the person she is today.

Lillis also said she won’t give up the battle for people to acknowledge that what is happening to her is real.

“I don’t let it get me down,” she said. “I’m so stubborn and I will fight this until the end.”