The United States has enacted many life-changing laws.

The thirteenth amendment abolished slavery in the country.

The fifteenth amendment gave every man, despite race, the right to vote.

In 1920, that right was extended to women by the nineteenth amendment.

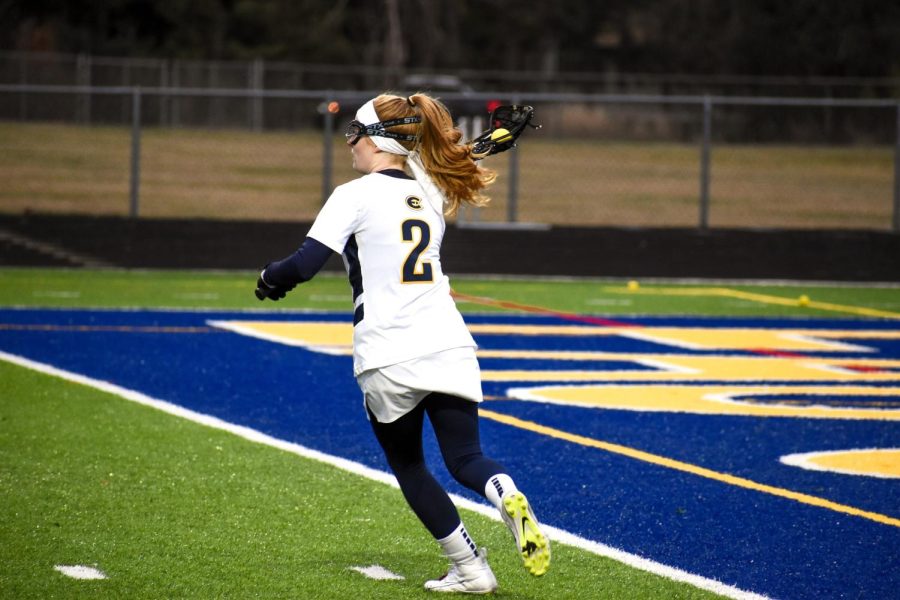

In 1973, Title IX was passed. The law ensured equality between men and women in federally funded educational programs. At the UW-Eau Claire, this especially applied to the athletic program.

2012 Eau Claire graduate and former softball player Ashley Rubenzer said how much the legislation paved the way for women in athletics and for women’s rights in general. She said she loves to see women’s sports have success.

“It is really sort of cool to see how effective (Title IX) has been,” Rubenzer said. “The funding being the same and the added sports have proven to be a move in the right direction. It’s cool to see not only the equality, but the successes that women teams have, especially at Eau Claire.”

She also said her professors and coaches throughout her athletic career at Eau Claire told her not to take what they had for granted.

“They would say, ‘when I was in school, we had awful equipment, played on crappy fields and didn’t have as many games as the guys,’” Rubenzer said.

When Mary Mero joined the athletic faculty in 1969, there were six women’s teams, gymnastics, swimming, diving, basketball, volleyball and track and field.

That was the first year there were women’s competitions at the university, she said. Without a federal requirement for university funding, the teams had next to no money, Mero said. The athletes bought their own uniforms and drove their own cars or carpooled to competitions, she said.

The women’s teams shared everything, Mero said. There was one set of women’s warm-ups that circulated between the six teams.

It wasn’t out of the ordinary for the different teams to carpool to out of town competitions together, she said.

The athletes rarely stayed anywhere overnight, because there was no money for hotels, many times not arriving back from competitions until 3 or 4 a.m., she said.

Even though they were competitors, teams from different schools frequently helped each other, Mero said. She recalls sleeping bags lining the floors of her own house when she hosted teams from out of town. When the Eau Claire women’s teams traveled, the other schools returned the favor, she said.

“That’s just the kind of stuff we did,” Mero said. “We did so much in helping and supporting each other, even those from other schools.”

In those early years, Mero, who coached the gymnastics team on top of teaching, said she did gymnastics sports camps. The first one, in 1969, was hosted partly because of changing rules and regulations of the sport, but also to raise money.

The money from those camps is what paid for the equipment for the team, she said.

It wasn’t until Title IX passed that things started to change for women’s teams.

“The women couldn’t even use the athletic training room because it was for men only,” Mero said. “When Title IX came in, that’s what changed the whole process.”

The change wasn’t instantaneous, she said. The first budget for women’s sports at the university was $500-700, she said. That amount had to be shared by all six women’s teams.

After Title IX passed, the university added women’s cross country, golf and softball. UW-Eau Claire also added a physical education major, specifically for women.

Before the law, women who wanted to major in physical education had to go to a different university, Mero said.

The women on faculty were expected to teach and coach, Mero said. She coached two teams and taught 28 credits each semester.

Being a coach was part of the job description, and they weren’t paid extra for it, she said.

Despite her busy schedule, Mero found time to serve as the national sports chair for the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for gymnastics.

She, along with many other women involved, thought the long hours were worth it, even when they faced opposition.

“We just said ‘this is what is going to happen.’ We had a reason for the madness,” Mero said. “You have to jump in and swim with the rest of them and that’s what we did. We had a passion.”

Women athletes and women faculty were still fighting for that passion when Jenny Arneson arrived at the university in 1980, Arneson said.

She was a runner for the university between 1980 and 1984, and then became the head cross country and track coach until leaving in 1996.

“It was an exciting time,” Arneson said. “It was several years after Title IX had come into play, but it was still the beginning years of women’s athletics in terms of the changes taking place.”

When her cross country team made it to nationals in Seattle in the ‘80s, there was still not an adequate amount of money in the budget to get them there, she said. They raised their own funds to get there and back by doing bake sales and asking family members for contributions, Arneson said.

Also in the early years of the cross country team, the women wore the old men’s uniforms, she said.

At that point, the law was requiring universities to fund women’s sports teams, Arneson said. Part was raising awareness and proving women had a spot in the athletic scene.

Once that happened, people were more willing to put their support, both financial and moral, behind the teams.

“I think part of gaining support is showing that women have the skills and the abilities to compete at a high level,” Arneson said. “The athletes at UW-Eau Claire certainly proved that.”

For those at the administration level, the work was going to budget meetings and pushing for more money, she said.

They had to “rehearse” their point over and over and had to continually stress women were deserving, Arneson said.

“It was meeting with the chancellors and the deans and those who were in positions of decision making and keeping awareness with them,” she said. “When it comes down to decision making for what should be funded and what needs to be cut, the awareness needed to be that women’s athletics and women’s athletes needed a place at the table.”

By the time she left the university in 1996, Arneson said the situation had improved “tremendously.”

Through the years, the financial support gradually but continually increased through their hard work, she said.

“Women student athletes today are in a lot better position and they should be,” Arneson said. “That’s through a lot of efforts of a lot of women raising awareness of the viability of women’s athletics.”