A ruptured aorta — it’s a fairly common injury in side-impact collision car crashes.

What’s not so common in the case of this injury, however, is finding your way to a hospital alive.

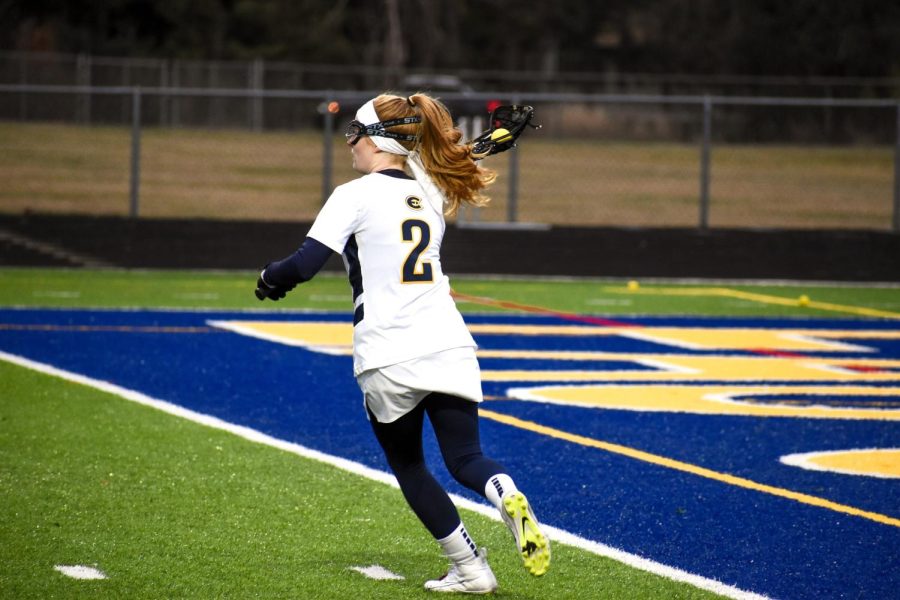

Michael Borglin, a fifth-year senior computer science major, was a junior running track and cross-country for UW-Eau Claire at the time of his accident.

After being rushed to medical attention by ambulance, he was told he would have a 5 percent chance of survival after tearing two of the three layers of the largest artery in his body.

En route for home after a weekend of competition, Borglin and several of his teammates were caught off guard by freezing rain, and blindsided by a van as they hydroplaned into oncoming traffic.

After regaining consciousness proceeding the impact, Borglin said the first place his mind had landed, after collecting his thoughts, was relief that he and his friends were okay.

“I remember thinking to myself that I wasn’t paralyzed and I didn’t see any blood … so I was probably okay,” Borglin said.

Unfortunately, Borglin would soon come to find this wasn’t the case — he had yet to realize the extensiveness of the crashes’ influence on his body.

“By the time I woke up the entire right side of the car where I was sitting was crushed,” Borglin said with an uneasy laugh. “The impact of the crash had crushed the car so much that my chair had shifted and I was sitting in the middle of the car.”

A day of what he said he thought would be nothing more than an opportunity to support his track team on the road ended in an incident that shook the entire university.

Flashing forward several months later, Borglin said he’d never imagined the possibility of suffering a broken pelvis, ruptured bladder and collapsed lung among a seemingly endless list of other injuries.

But in the moment, he said he recalls hearing his teammate yelling for him to leave the car, as the back-seat passengers were pinned inside. Despite feeling numb enough to consider himself okay, Borglin realized he wouldn’t have the strength to remove his seat belt.

The rest, including the following two weeks of his life, is a blur.

As daunting as fighting the odds of this accident, his injuries and the resulting coma seems from an outside perspective Borglin said calmly that he looks back now after a year and a half of recovery on the most trying part of his various operations, his heart surgery, with optimism.

Borglin said his optimism came in part from those who supported him diligently, including his family, coaches and friends. Before his family had even managed to arrive, head track and field coach Chip Schneider was at his side.

“I developed a tradition of rubbing Chip’s head before races for good luck because he’s bald,” Borglin said with a grin. “So when he made it to the hospital I rubbed his head hoping for some of that luck in my surgeries.”

Borglin’s cross country coach, Dan Schwamberger, mirrored Schneider in leading their teams’ support of their fellow runner.

“We get so into the season and focused on our running … so thinking for a time that there was a possibility we were going to lose him was a reality check,” Schwamberger said. “It kind of made everyone take a step back and realize how fortunate we all have it.”

While he said the process was gradual, Borglin managed to find his way back to campus the following semester, easing his way into academia by enrolling part-time. Patience was still the name of the game for him as his consistently postponed heart operation loomed around the corner.

Borglin said there was plenty of room for error in his upcoming surgery haunting him during his wait.

He acknowledged incorrect procedures during the surgery would mean a 20 percent chance of never being able to run competitively again as a result of irregular heart beats, as well as a 15 percent chance he’d need a pacemaker for the rest of his life.

During this time, Borglin was accompanied most frequently by his best friend Shannon Feil. While not blood related, Borglin said he considers Feil as close as family — so close that she spent all of his thirty-four hospitalized days with him.

“I actually faked being his sister so that I could get into the hospital,” Feil said. “At least in my time there I saw that there are small comforts for patients to get by with … seeing who came to visit him was definitely a part of that.”

Even with the support of his friends and family, Borglin said there were times when he couldn’t force back his nervousness about the uncertainty of his future.

“I remember a night when I saw my heart rate three times what it normally was,” Borglin said. “I forced myself to ask the nurse for a sheet of paper so that I could write my will out … obviously I don’t have many belongings at my age but I wanted to let my friends and family know that I love them.”

But despite being forced to put his life on hold, Borglin eventually succeeded in surviving and recovering — so successfully that those who haven’t heard his story wouldn’t know a difference.

Waiting for his heart to recover meant an inability to support the Blugolds in competitive races, but Borglin said he was committed to continuing his involvement with both of his teams. Instead of running, his role shifted to supporting from the sidelines.

“I’d go up to the track and see everyone running and I wanted it for myself so bad,” Borglin said. “But it was nice enough to live vicariously through my teammates … I wasn’t totally cut off.

“When I was in the hospital I think one of the things that got me through it was this delusional resolve of success,” Borglin said. “I have this mentality that I will succeed … and there’s no questioning that.”

Today, Borglin is approaching his graduation date and hard at work on completing his computer science degree. Although his time as a Blugold is coming to an end, Borglin said his running career has just begun — he hasn’t forgotten his years of eligibility still available.

“A huge part of who I am as a person is being a competitive runner,” Borglin said. “Now that I know I have a strong heart again I’ll be able to get back to what I love.”

Borglin said he and Schwamberger entertain the idea of his someday coming back to capitalize on these unused years he’ll hold in his back pocket if he chooses to continue his education.

Until then, Borglin will continue on running and computing just as he had before his accident — not forgetting what he’s experienced, but also using the strength it’s given him along the way.